Newly freed slaves in 1865 found themselves in uncharted waters. Most had no concept of regimented schooling, especially in a time when the policy towards slaves was strictly no-education-ever. But the end of the Civil War brought hope and aspiration never before seen; and, under those circumstances, the first independent institution for higher learning was opened in Florida. Better yet, it was started to educate those who previously had been barred from the ivory towers of academia.

Newly freed slaves in 1865 found themselves in uncharted waters. Most had no concept of regimented schooling, especially in a time when the policy towards slaves was strictly no-education-ever. But the end of the Civil War brought hope and aspiration never before seen; and, under those circumstances, the first independent institution for higher learning was opened in Florida. Better yet, it was started to educate those who previously had been barred from the ivory towers of academia.

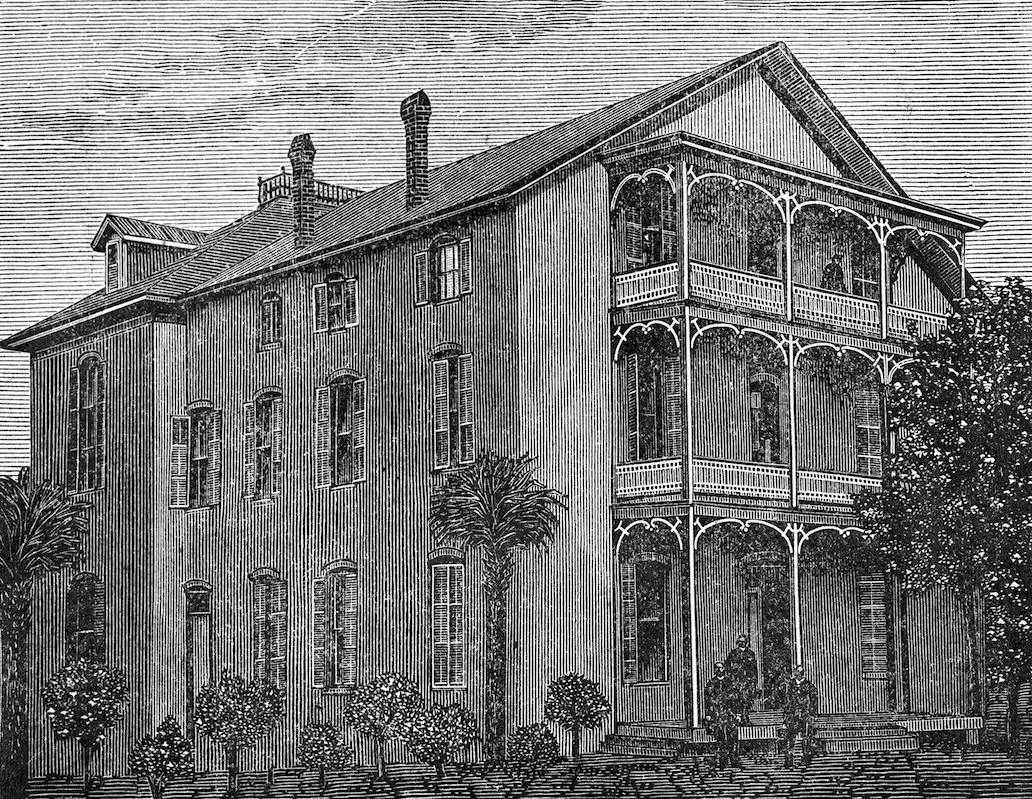

Edward Waters College opened its doors in 1866 in Live Oak. Lillie Vereen, current Edward Waters College alumni president, graduated from the school in 1969. As part of her tenure as president, she has been a driving force in raising local, regional and national awareness of the school. In 2016, she led a coalition to place a historical marker on the site of the original campus in Live Oak, a small town west of Jacksonville.

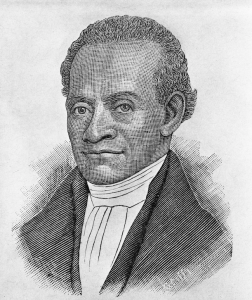

“The most beautiful part of the history of this school is that someone thought it worthwhile to educate freed slaves; someone cared enough about the most disenfranchised of people,” Vereen says. Initially opened as the Brown Theological Institute, the first few years of the institution were tumultuous. Funding was difficult to procure and students hard to come by. “The first programs offered were general education programs, teacher training and a seminary program tied to the nation-wide congregation of the African Methodist Episcopal, better known to this day as the AME Church,” Vereen says. Reverend Charles H. Pearce had been sent to Florida from Philadelphia during Reconstruction to build a congregation for the AME Church. He succeeded in establishing the first independent black denomination in the United States.

Reverend Pearce had been born into slavery in Maryland and bought his freedom as an adult. Educated in Connecticut and Canada, Pearce understood the significant role education would play in the lives of newly freed men and women and what that could mean socially and economically for a downtrodden group emerging from servitude, beset with a legacy of poverty and illiteracy. The initial funding from the AME Church would help swing the doors of the school open, but many hardships still loomed ahead.

Reverend Pearce had been born into slavery in Maryland and bought his freedom as an adult. Educated in Connecticut and Canada, Pearce understood the significant role education would play in the lives of newly freed men and women and what that could mean socially and economically for a downtrodden group emerging from servitude, beset with a legacy of poverty and illiteracy. The initial funding from the AME Church would help swing the doors of the school open, but many hardships still loomed ahead.

Some three to four years after the school was founded it abruptly closed. Securing ongoing funding proved difficult and expecting the majority of students—ex-slaves—to pay their own way was unrealistic. The idea of the college, while admirable, seemed doomed. Yet hope, and financial support arrived in the form of a few investors who would help solidify the future of the Brown Theological Institute.

General Milton S. Littlefield had earned his fortune in the railroad business. The New Yorker had organized a company of infantry at the onset of the Civil War in 1861 and had served in the mid-Atlantic before being sent South to briefly command the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first colored unit of the Union, made famous in modernity by the film Glory. General Milton’s reputation was not sacrosanct, as he was embroiled in accusations of post-war profiteering. Still, alongside Florida politicians, Lieutenant General William Gleason and State Treasurer Simon Conaber, the school re-opened in the late 1870s on a 10-acre campus in Live Oak.

The school would relocate to Jacksonville in 1883 and assume the name East Florida Conference High School and later as the East Florida Scientific and Divinity High School. The move to Jacksonville had uncertain drivers, yet could certainly be attributed, in some part, to Reverend Pearce spending much of his time in the city.

By 1892, the established school was receiving increased financial support from the AME Church again and it was renamed after the third bishop of the AME Church, Edward Waters. The campus buildings would succumb to the flames of the Great Fire of 1901. New land was secured in 1904—and it remains today at that same location.

“I carry the EWC Alma Mater in my heart. Throughout the history of this school the professors have been engaged and have made sure that students advance. When I was there it was a family affair,” Vereen says. “After all these years and all the advancements in technology, the school has grown and matured, but the spirit of the school remains the same.”