Rapid population growth is putting the squeeze on Florida’s wild lands and the animals that inhabit them. However, a vast patchwork of public and private lands collectively known as the Florida Wildlife Corridor aims to sustain the state’s wild places and, in the process of doing so, save some 700 imperiled species of animals and plants. In what may be a surprise, in many ways the plan is working.

A Florida black bear is a creature that appreciates opens spaces and room to roam. In fact, a male Florida black bear, of which more than 4,000 are believed to wander the state, requires about 60 square miles of flatwoods, swamps, scrub oak or hammock in which to forage for food. For most of the year, individual bears stay in their home territory, constantly on the move for wild berries, acorns and other food sources but not venturing far from their dens. However, it’s not uncommon for one to set out on a cross-state journey.

About 15 years ago, researchers placed a GPS tracking collar on a bear they tagged as “M34.” The 190-pound male was tracked for eight months, always staying relatively close to his forest capture site in south central Florida. Then, one day in May, he abruptly left his traditional home range. For the next two months, M34 was in near-perpetual motion. He crossed rivers and highways, skirted the edges of towns, and swam in lakes, before eventually spending a week in the company of female bears on a pair of ranches near Lake Okeechobee.

About 15 years ago, researchers placed a GPS tracking collar on a bear they tagged as “M34.” The 190-pound male was tracked for eight months, always staying relatively close to his forest capture site in south central Florida. Then, one day in May, he abruptly left his traditional home range. For the next two months, M34 was in near-perpetual motion. He crossed rivers and highways, skirted the edges of towns, and swam in lakes, before eventually spending a week in the company of female bears on a pair of ranches near Lake Okeechobee.

For the researchers, his journey was fascinating to follow. Tracking his path provided all sorts of new information, specifically where he went, the route he traveled to each location and how long he stayed in one place before moving on. In addition, the scientists got a bears-eye view of the state and the land he used to survive. They discovered that the connections between wild spaces were crucial to M34’s travels. The farms, ranches and undeveloped property were just as important as protected forests and other preserved wilderness. These “corridors” made his two-month journey possible.

Mallory Dimmitt, CEO of the Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation (FWCF), has been involved in the initiative since inception and has ridden horses, hiked, biked and paddled hundreds of miles across the state. She recalls how that one bear’s adventure led to the creation of the group. “The idea was inspired by M34. He went on a 500-mile walkabout in 2010.” So, she and a pair of other conservationists decided to undertake one of their own.

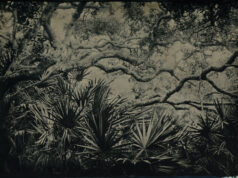

In 2012, Dimmitt, acclaimed photographer Carlton Ward and filmmaker Elam Stoltzfuz trekked from Everglades National Park to the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. The journey took 100 days and didn’t end until they had crossed into Georgia. “It was an incredible experience,” she says. “I remember every day,” adding the most dangerous part of the trip was not wading through swampy waters but biking on paved roads.

The Florida Wildlife Corridor is a patchwork of properties that stretches across the entire state. Think of it as a network of connected open spaces spanning nearly 18 million acres, or what equates to some 40% of the state. That’s a lot of land, for sure. But there are holes in the quilt, places where connections still need to be made.

Approximately half of the land is wilderness, solidly locked up as conservation acreage, either owned by environmental organizations or state of federal agencies. The remaining 8.1 million acres is a mix of privately held property and government-owned land. A sizable amount of the land is open for public use for camping, fishing and hiking. There are more than 5,800 miles of trails within the Corridor, as well as 1,323 named rivers and streams that include over 1,500 miles of paddling waters.

Approximately half of the land is wilderness, solidly locked up as conservation acreage, either owned by environmental organizations or state of federal agencies. The remaining 8.1 million acres is a mix of privately held property and government-owned land. A sizable amount of the land is open for public use for camping, fishing and hiking. There are more than 5,800 miles of trails within the Corridor, as well as 1,323 named rivers and streams that include over 1,500 miles of paddling waters.

Much of the Corridor’s land is situated within the guarded boundaries of some of Florida’s many military installations. Camp Blanding Joint Training Center, for example, is located west of Jacksonville near the town of Starke. The crystal-clear waters of Kingsley Lake have been a magnet for boaters and fishermen for generations, and part of the base spills right into its spring-fed waters. Most of Camp Blanding’s 73,000 acres,

however, are sandy pine forest, undeveloped land that is used by the Florida National Guard and other federal and state agencies for training. Despite the occasional rumble of Humvees and helicopters clattering overhead, the forestland makes for suitable habitat for all sorts of animals while, at the same time, providing a natural bridge to the nearby Raiford Wildlife Management Area and Jennings State Forest.

This dual-use concept for military property serving as a haven for nature is known in government parlance as a Sentinel Landscape. In Florida, these landscapes can be enormous. The Avon Park Air Force Range Sentinel Landscape, located in the center of the state and due east of Vero Beach, covers approximately 1.7 million acres. It is anchored by the Air Force’s largest air-to-ground training range east of the Mississippi River and is used by every branch of the Armed Forces. At the same time, it is home to numerous private cattle ranches and it is prized in environmental circles for its rich biodiversity.

Journey over to Florida’s Panhandle for the Northwest Florida Sentinel Landscape, another huge swathe of longleaf pine forests, agricultural lands and threatened and endangered species habitat. Also peppered across the region are nine Department of Defense installations and ranges used for special operations training, weapons testing, and aviation training for the Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps.—all of which cohabitate with natural resources including the Apalachicola National Forest, Black Water River State Forest and St. Vincent National Wildlife Refuge.

Research estimates that the Corridor not only provides inherent scientific, recreational, and cultural value, but also supports significant economic activities. In fact, according to McKinsey & Company analytics, the lands support at least 114,000 jobs and provides $30 billion in annual value in sectors such as recreation, tourism, and agriculture including ranching and forestry. In addition, and arguably far more important, it simply helps provide a place to live for some of the state’s most precious wildlife. The Corridor is home to 60 species at-risk of extinction, such as the grasshopper sparrow and the Florida panther.

Research estimates that the Corridor not only provides inherent scientific, recreational, and cultural value, but also supports significant economic activities. In fact, according to McKinsey & Company analytics, the lands support at least 114,000 jobs and provides $30 billion in annual value in sectors such as recreation, tourism, and agriculture including ranching and forestry. In addition, and arguably far more important, it simply helps provide a place to live for some of the state’s most precious wildlife. The Corridor is home to 60 species at-risk of extinction, such as the grasshopper sparrow and the Florida panther.

“Timber operations might not be great habitat, but they allow for animals to move through them,” says Dimmitt. “We proved you can link together all of these lands. While on its own, a piece of property might not have much value. But even a power line right-of-way can be part of the solution.”

Even as Florida’s population increases by about 1,000 people each day, the state’s efforts to preserve land has shown significant promise. “Florida has some of the greatest land conservation east of the Mississippi,” says Dimmitt. “We are still in a race to protect the corridor, particularly 900,000 acres that are our highest priority and at most risk to development.” Open spaces on the outskirts of Orlando, in particular, are among the most vulnerable to being lost.

In March of this year, seven parcels of land totaling 16,706 acres within the Florida Wildlife Corridor were approved for acquisition and conservation easement. The properties were specifically selected because they address important conservation focuses within the state, including archeological and prehistoric sites and protection of at-risk species. “This $32-million public investment is a huge step toward preserving key linkages throughout the Florida Wildlife Corridor,” says Jason Lauritsen, chief conservation officer of the FWCF. “Approval will further protect wildlife and safeguard water supplies for residents and visitors. We hope that these acquisitions and conservation easement agreements close smoothly and swiftly and that we continue marking substantial progress through regular additive conservation action that will protect the Florida Wildlife Corridor for generations to come.”

Three months later, Governor Ron DeSantis signed The Florida Wildlife Corridor Act, a piece of legislation that directs the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to encourage and promote investments in areas that protect and enhance the Corridor. $300 million was budgeted specifically to fund the efforts. In all, a total of 36,445 acres of land will be protected through public investment by the State.

The Foundation doesn’t own any property. Instead, it works as an advocate and in partnership with those who do—meaning everyone from private cattle ranchers to timber harvesting companies to myriad branches of the government and environmental organizations ranging from the U.S. Forest Service to The Nature Conservancy.

The Foundation doesn’t own any property. Instead, it works as an advocate and in partnership with those who do—meaning everyone from private cattle ranchers to timber harvesting companies to myriad branches of the government and environmental organizations ranging from the U.S. Forest Service to The Nature Conservancy.

“I thank Governor DeSantis and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection for their investment in the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act,” says Ward, a founder of the FWCF and the Path of the Panther project. “Through their leadership, Florida will set a global example for how world-class natural areas, like the Everglades—rare and endangered wildlife like the Florida panther—and a robust and growing economy can thrive together.”

“Protecting essential Florida lands and waters is necessary not only to the Florida panther, black bear, red cockaded woodpecker, gopher tortoise, longleaf pine and so many others that depend on those lands to move, grow, and prosper in Florida, but also for our ability to successfully mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change,” says Temperince Morgan, executive director of The Nature Conservancy in Florida. “There is great economic opportunity in the preservation of our natural places, and the importance of access to nature for our physical and mental wellbeing, as well as for recreational opportunities cannot be understated.”

In a rare instance of government agreement, the initiative received bipartisan support. “Our children and grandchildren deserve to know, and enjoy, the same beautiful Florida that we do,” says House Speaker Chris Sprowls. “This landmark legislation will ensure that Florida’s distinctive ecosystem continues to flourish. Governor DeSantis has made a sensible, solution-oriented environmental policy a priority during his time in office and along with [Florida Senate President] Wilton Simpson’s expertise with agriculture and conservation planning, we were able to pass this important bill unanimously through the legislature.”

To learn more, visit FloridaWildlifeCorridor.org.